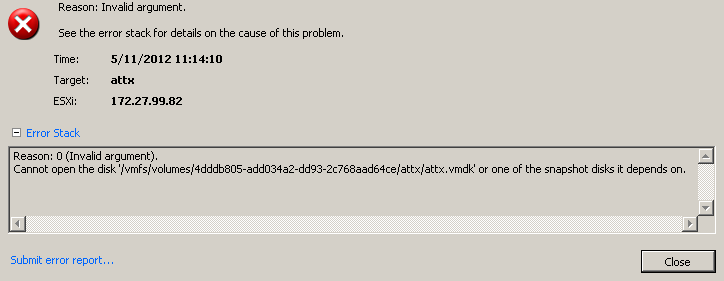

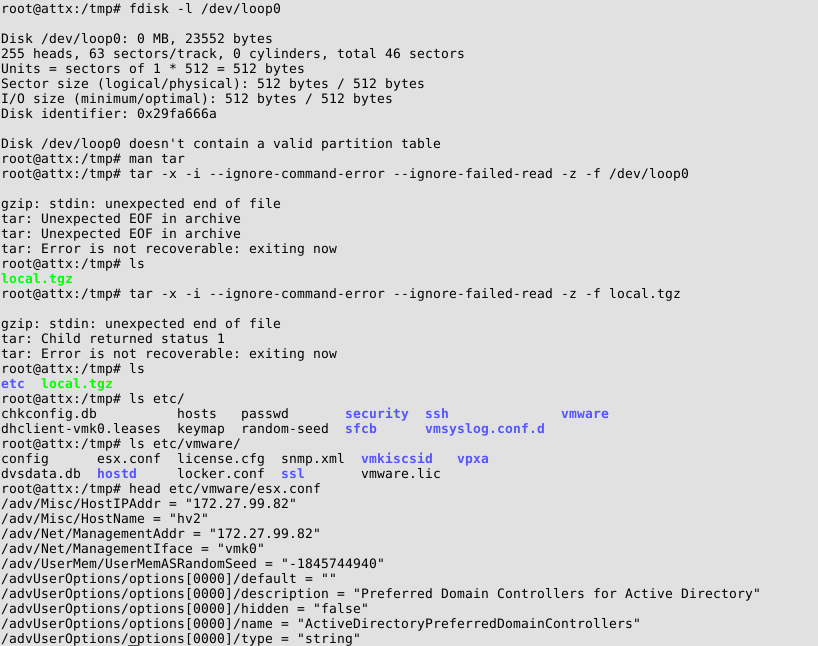

As announced at last week’s #HITB2012AMS, I’ll describe the fuzzing steps which were performed during our initial research. The very first step was the definition of the interfaces we wanted to test. We decided to go with the plain text VMDK file, as this is the main virtual disk description file and in most deployment scenarios user controlled, and the data part of a special kind of VMDK files, the Host Sparse Extends.

The used fuzzing toolkit is dizzy which just got an update last week (which brings you guys closer to trunk state 😉 ).

The main VMDK file goes straight forward, fuzzing wise. Here is a short sample file:

# Disk DescriptorFileversion=1encoding="UTF-8"CID=fffffffeparentCID=ffffffffisNativeSnapshot="no"createType="vmfs"# Extent descriptionRW 40960 VMFS "ts_2vmdk-flat.vmdk"# The Disk Data Base#DDBddb.virtualHWVersion = "8"ddb.longContentID = "c818e173248456a9f5d83051fffffffe"ddb.uuid = "60 00 C2 94 23 7b c1 41-51 76 b2 79 23 b5 3c 93"ddb.geometry.cylinders = "20"ddb.geometry.heads = "64"ddb.geometry.sectors = "32"ddb.adapterType = "buslogic"

As one can easily see the file is plain text and is based upon a name=value syntax. So a fuzzing script for this file would look something link this:

name = "vmdkfile"

objects = [

field("descr_comment", None, "# Disk DescriptorFile\n", none),

field("version_str", None, "version=", none),

field("version", None, "1", std),

field("version_br", None, "\n", none),

field("encoding_str", None, "encoding=", none),

field("encoding", None, '"UTF-8"', std),

field("encoding_br", None, "\n", none),

[...]

]

functions = []

The first field, descr_comment, and the second field, version_str, are plain static, as defined by the last parameter, so they wont get mutated. The first actual fuzzed string is the version field, which got a default value of the string 1 and will be mutated with all strings in your fuzz library.

As the attentive reader might have noticed, this is just the first attempt, as there is one but special inconsistency in the example file above: The quoting. Some values are Quoted, some are not. A good fuzzing script would try to play with exactly this inconsistency. Is it possible to set version to a string? Could one set the encoding to an integer value?

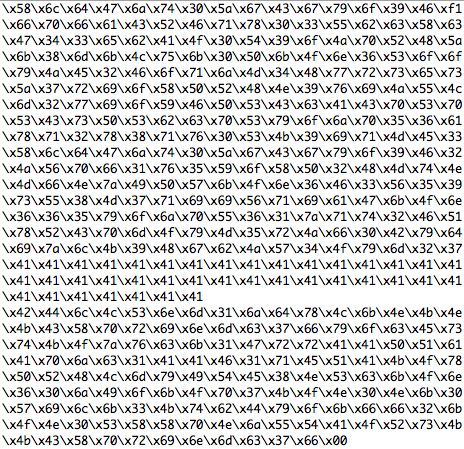

The second file we tried to fuzz was the Host Sparse Extend, a data file which is not plain data as the Flat Extends, but got a binary file header. This header is parsed by the ESX host and, as included in the data file, might be user defined. The definition from VMware is the following:

typedef struct COWDisk_Header {

uint32 magicNumber;

uint32 version;

uint32 flags;

uint32 numSectors;

uint32 grainSize;

uint32 gdOffset;

uint32 numGDEntries;

uint32 freeSector;

union {

struct {

uint32 cylinders;

uint32 heads;

uint32 sectors;

} root;

struct {

char parentFileName[COWDISK_MAX_PARENT_FILELEN];

uint32 parentGeneration;

} child;

} u;

uint32 generation;

char name[COWDISK_MAX_NAME_LEN];

char description[COWDISK_MAX_DESC_LEN];

uint32 savedGeneration;

char reserved[8];

uint32 uncleanShutdown;

char padding[396];

} COWDisk_Header;

Interesting header fields are all C strings (think about NULL termination) and of course the gdOffset in combination with numSectors and grainSize, as manipulating this values could lead the ESX host to access data outside of the user deployed data file.

So far so good, after writing the fuzzing scripts one needs to create a lot of VMDK files. This was done using dizzy:

./dizzy.py -o file -d /tmp/vmdkfuzzing.vmdk -w 0 vmdkfile.dizz

Last but not least we needed to automate the deployment of the generated VMDK files. This was done with a simple shell script on the ESX host, using vim-cmd, a command line tool to administrate virtual machines.

By now the main fuzzing is still running in our lab, so no big results on that front, yet. Feel free to use the provided fuzzing scripts in your own lab. Find the two fuzzing scripts here and here. We will share more results, when the fuzzing is finished.

Have a nice day and start fuzzing 😉

Daniel and Pascal

Continue reading

A quick update on the workshop we’ve just finished at

A quick update on the workshop we’ve just finished at